The life and service of Constable John Hillis of Lanarkshire Constabulary during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

CONSTABLE JOHN JAMES HILLIS

DUBLIN METROPOLITAN POLICE – 1861 to 1867

LANARKSHIRE CONSTABULARY – 1867 to 1907

John James Hillis was born in the Parish of Ardtrea, Stewartstown in County Tyrone, Ireland in 1842. His father was a farmer. John was brought up and educated in the local area, leaving school at 12 years of age to work on the farm with his father, as a farm labourer.

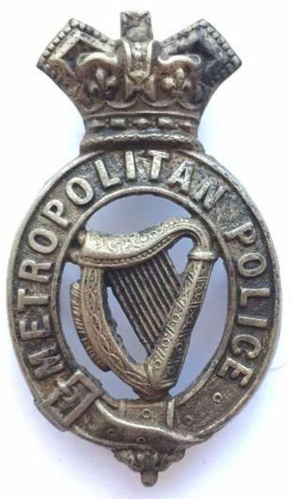

Dublin Metropolitan Police Badge

On the 30th of May 1861, at the age of nineteen, John travelled to Dublin where he joined the Dublin Metropolitan Police. He was allocated service number 6298. During the period of his service there were Nationalist tensions in Dublin and throughout the country.

John was one of the officers involved in a raid on the Irish People Newspaper on Thursday the 15th of September 1865. The paper had been publishing articles which were considered to be the cause of the tensions, and it was learned that the editors were instrumental in planning an Irish uprising against the British Government. The order was given to raid their premises and close the paper down, which they did. The editors were subsequently arrested.

One of the editors, Thomas Clarke Luby, was sentenced to 20 years penal servitude. He was released in 1871 but could not return to Ireland. He later settled in America, travelling the country lecturing about Ireland and writing political pieces in various publications. He died in Jersey City in 1901.

John Hillis remained in the Dublin Police until he discharged himself on the 2nd of July 1867. He left the country, travelling to Scotland, settling in Lanarkshire.

Almost immediately on his arrival he joined Lanarkshire Constabulary and was posted to Hillhead, which at that time was an independent Burgh policed by Lanarkshire Constabulary. In addition to John there were thirteen other Constables.

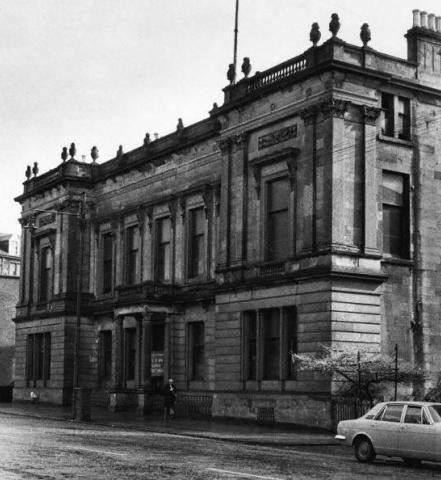

Hillhead Burgh Halls & Library and old Police Station

Here he had his first experience of the ways of the Glasgow criminal. Two men apparently assisting a companion home attracted his attention in the early hours one morning. Challenging them, he was informed that they were taking the man home to his house in Partick. At that he allowed them to proceed, but a minute or two afterwards the suspicion returned to his mind that all was not right, and he made after the trio once more.

This time the two men bolted, and Constable Hillis giving chase, landed them in the outstretched arms of another policeman. Then it was found that the third man had been assaulted and robbed by the two notorious Glasgow criminals.

On another occasion his intuition led to the arrest of two Dundee housebreakers that had been reaping a harvest in Glasgow. Having a quiet smoke one morning along with the sergeant of the beat, his attention was attracted to two men coming up the road at Kelvinside Church. He suggested to the sergeant that he might stop one of the men, leaving the other to him, and they would see what they were up to.

Suspicious of the pair the two officers stopped and searched them finding no fewer than 51 false keys were found in their possession. They had just committed a burglary in the city centre in the early hours and were heading to the West End to plunder some of the mansions of Dowanhill.

The year 1875 is memorable in the annals of the burgh of Partick from the party riots that raged for three days in that district. The riots broke out on the 6th of August , sparked by Irish celebrations of Daniel O’Connell’s centenary, the Partick police were quickly overwhelmed.

Partick was still a small independent Burgh police force and had to call on the assistance of other forces such as Lanarkshire Constabulary and The City of Glasgow Police. In addition, to bolster their ranks, the burgh authorities swore in around 30 local residents as special constables. Among these was the now-legendary Rachel Hamilton, aka “Big Rachel,” whose imposing stature, she was six foot four inches and nearly 17 stones, and local respect made her a formidable presence on the streets.

Constable Hillis was one of the Lanarkshire Constabulary men drafted into the effected district, performing duty in the vicinity of Partick Cross. There the Riot Act was read by Sheriff Murray after churches, shops and other property had been wantonly destroyed.

The police were subjected to rough treatment over several days with many being seriously injured, this necessitated the free use of the baton. The riots eventually came to an end through a mix of community intervention, emergency policing, and sheer force of will by the authorities. However, the effects of the riots left a long-standing impact.

From Hillhead, Constable Hillis was transferred to South Lenzie (Cadder) in May 1877. Prior to that time the district had had no resident constable, being patrolled from Muirhead. At that time, it was only a fraction of its present size, but growing rapidly, hence the appointment of Constable Hillis.

The police house was located in Burnbank Terrace on Auchinloch Road, and was distinguished by the enamelled sign stating, “County Police”. Constable Hillis remained there until his retirement when he then moved to nearby Glenbank Road.

Burnbank Terrace

Lenzie was not particularly notorious for crime in those years however Constable Hillis certainly kept himself busy.

Constable Hillis paid particular attention to the ‘foreign’ element from out of town. It was then that the well-known character, William ‘Wull’ Stirling, who held the Kirkintilloch Police Court attendance and conviction record, fell into his hands. Wull had well over 70 convictions against his name at that time, although none of them were for theft, although this possibly meant that he had never been caught!

On a particular day a washing, drying on a wayside hedge, was too much of a temptation for Wull and he swiped the men’s clothing from the hedge. The theft was reported t Constable Hillis.

Later in the day Wull was spotted by Constable Hillis walking through Lenzie, resplendent in his new clothing, which was a surprising sight considering his usual attire, it also bore a striking resemblance to items stolen earlier in the day!

John stopped him and quickly established that the clothing stolen from the hedge. Wull was arrested and kept in custody for his court appearance.

Things happened quickly in those days, and he appeared the following day. Constable Hillis escorted Wull toward the Sheriff Court when Wull requested a chew of tobacco. The Constable obligingly gave him some. whereupon, with an expression of appreciation of his decency, Wull announced that he would plead guilty.

When the charge was being read out Wull glanced around the court, and seeing nobody whom he took to be a witness , he replied to the charge, ” Not Guilty”, much to the surprise of Constable Hillis.

However, what Wull didn’t know was that the witnesses were in the entrance to the court, out of his sight. They were duly called gave their evidence, identifying the stolen clothing. Wull thereafter received his first conviction for theft and went to prison for 15 days.

Another clever bit of work led to a man getting five years’ penal servitude in 1877. Late one evening a man arrived at Lenzie with a flock of sheep, to be sent by train to Edinburgh. Constable Hillis engaged in conversation with the man and asked him about the sheep, which the man said were his.

On being more closely pressed, he actually admitted that they weren’t his and that the sheep had been entrusted to him by a Kippen farmer, and that he would have to wait overnight for a train. The man was given permission to the sheep in a field for the night and the man found nearby lodgings.

Constable Hillis meanwhile made contact, by telegraph, with the Constable at Kippen. Local enquiry could not trace a farmer who had requested anyone to take sheep to Edinburgh.

Early the following morning Constable Hillis, as was his normal habit, read the morning newspapers for useful information. His attention was drawn to an article relating to a wanted man in Renfrewshire for the audacious theft of sheep from Crosshill, Renfrewshire. The description of the wanted man fitted perfectly the man Constable Hillis had spoken to in Lenzie. He immediately tracked him down and arrested him. The Renfrewshire Police were contacted and uplifted the man and the sheep.

The man later appeared at the High Court in Glasgow before Lord Deas, who took a serious view of the case as to impose five years penal servitude on the man.

The following year, 1878, saw Constable Hillis engaged in an altogether different duty. That year the then Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII, paid a long-anticipated visit to the Duke of Hamilton, whose shooting parties were preserved for the sport of the Royal family for many years.

Constable Hillis was one of 16 men selected for the prince’s bodyguard, following him wherever he went.

His next serious encounter with Kirkintilloch criminals was in connection with an extensive theft of poultry. The snow lay deep on the ground, and Constable Hillis was able to trace the thieves by a trail of blood down the Monkland Railway to Kirkintilloch.

Two notorious thieves living in the Hillhead district were suspected of the thefts. Accompanied by a Kirkintilloch policeman a visit was paid to the house of one of them. The suspect was not at home, and a thorough search of the house failed to find any of the stolen poultry.

However, the chance remark of an old weaver, as they were leaving the house, caused Constable Hillis to return to the house, and search again. In the loft they found a trap door they found a large bag of dead chickens. The culprit was eventually traced by Constable Hillis and Inspector Murray. However, the man fought violently attacking the officers with an iron bar, narrowly missing the Inspectors head. He was eventually overpowered and arrested. He was charged and later sentenced to four months imprisonment.

From the summer of 1886 through to August 1887 there were a series of housebreakings in the Glasgow, Renfrewshire, Dunbartonshire and Lanarkshire areas. The police, despite considerable effort, were unable to trace the culprits.

Constable Hillis dealt with the Lanarkshire crimes in his area, which were in Victoria Road, Lenzie and Auchinloch. A considerable amount of money and property was stolen.

Constable Hillis made extensive enquiries, recovering over £25 worth of property as far away as Kinsale in County Cork. His investigations provided the names of those involved, who were notorious housebreaker David Napier McGregor and his associates Margaret Fernie, James McGiffen, and John Hardie.

The four were eventually caught in August 1887 by the City of Glasgow Police. They appeared at The High Court in Glasgow in October 1887, when McGregor was sentenced to 10 years imprisonment and the others to 18 months imprisonment.

Constable Hillis also had the distinction of having the first case in Scotland under the Wild Birds Protection Act. Making a midnight visit to the bothy at Lumloch Pit (later named Wester Auchengeich) he found two men asleep. A bag lying near the men attracted his attention, the chirping of birds being clearly audible. He found a dozen birds in the bag.

The men were arrested under the Trespass Act, and it was afterwards proved against them that the previous evening had been spent in netting the adjoining fields for larks. The men were fined 3shillings for each bird.

In 1894, John’s wife Elizabeth died of cancer.

In November 1898, he re-married. His new wife, Alice George, was a widow.

Constable Hillis thoroughly enjoyed his 46 years of police service until his retirement on Tuesday the 6th of August 1907, severing his connection with the Lanarkshire Constabulary, which extended for over 40 years.

He was described in a local newspaper – “Senior Constable Hillis is hale and hearty and apparently fit for a good many years’ activity yet. Mr Hillis is of a quiet, civil, courteous disposition, and has made many friends in the district, who will wish for for him a long enjoyment of his well-earned retirement”.

Constable Hillis was replaced by Constable William Edward who was previously stationed at Leadhills.

John remained in the Lenzie area. Sadly, his second wife died in 1916 and John died in 1928 at the age of 85 years. In his will, he left £256 (£13,934 today) to his family of two sons and a daughter.